Pilot Peak, Beartooth Range, Greater Yellowstone. Photo: Jeffrey St. Clair.

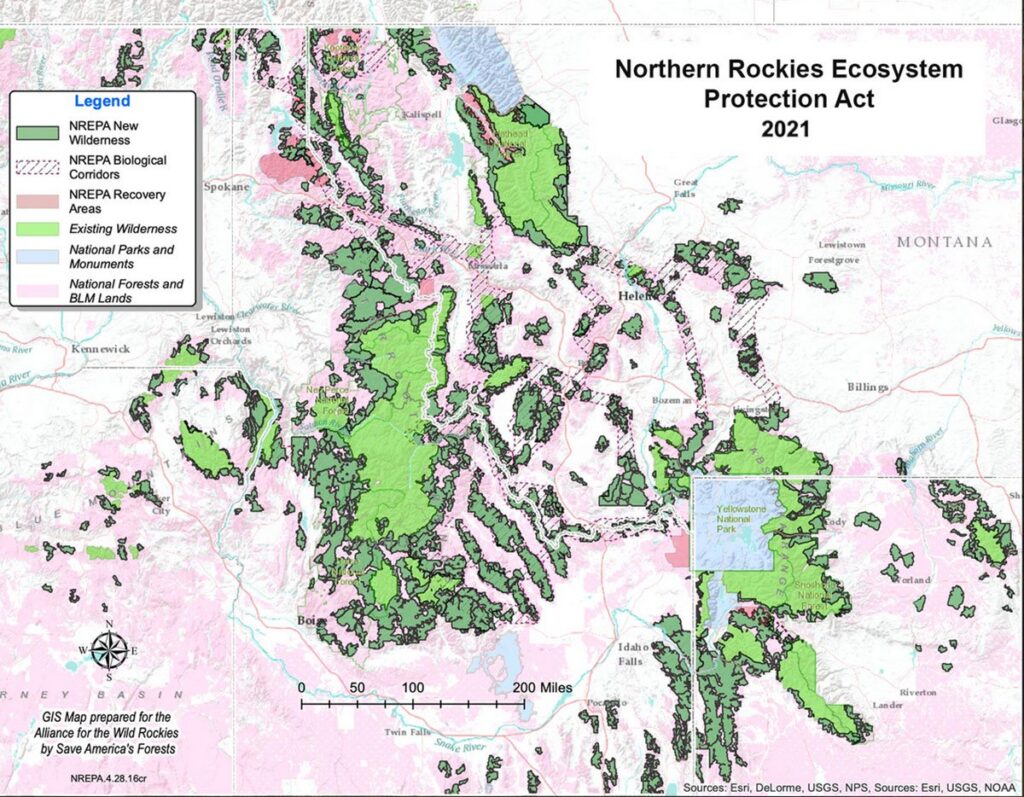

If ever there is a time for cooperative ecological action it is now, and there are plenty of opportunities for engagement in the West. The Rocky Mountain system/ Wild Rockies bioregion spans six states (New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho and Montana.) Five of these Northern Rockies ecosystems– Greater Yellowstone, Hell’s Canyon-Wallowa, Salmon Selway, Glacial Northern Continental Divide, and Cabinet-Yaak-Selkirk– comprise the focus of the Northern Rockies Environmental Protection Act (NREPA), sponsored by the Alliance for the Wild Rockies (the Alliance).

Founded in Missoula, Montana during the Reagan-Bush Era, the Alliance is a leading voice for regional environmental policy and action. With Montana alone hosting five million plus visitors annually, as tourism ensures local and regional economies remain in dying nature’s death-grip, local officials ignore the big picture and skirt routine democratic processes to expedite extraction. One recent example is the decision to surpass public review in Montana Democratic Senator Tester’s Blackfoot-Clearwater Stewardship (Stumps) Act. This Act opens 49,000 roadless forest acres to a series of smaller (3,000 acre max) logging projects, bypassing standard Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) and Environmental Assessment (EA) procedures.

In the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE), officials favor wildlife slaughters and egregious logging/mining development projects continue. Alston Chase’s Playing God in Yellowstone (1987) shockingly recorded Park officials’ devastating management culture. They made a mockery of a Native American tradition and steered animals off cliffs. An apt metaphor, “steering animals off cliffs” describes Park management strategy well. They practiced so-called natural control and regulation relying on traps, tags and exclosures and organized pelt and meat slaughters. The 1970s “ecosystems management” era preached holism but continued arbitrary slaughters of predators and prey. The environmental era has cast a green aura around the Park for all its natural wonders, but the same old blame-punish-exterminate-system remains.

As Yellowstone goes, so goes the nation. Yellowstone’s practices mirror general views towards wilderness, wildlife and park management and realities.

Overwhelmed by federal and state mismanagement, species endangerment, headwaters pollution and roads/logging/ mining threats– regional organizations strategize to preserve remaining ecosystem health. The Alliance’s mission to “secure the ecological integrity of the Wild Rockies bioregion through citizen empowerment and the application of conservation biology, sustainable economic models and environmental law” addresses the ticking time bomb of climate catastrophe head-on with an agenda. This just as more people strategize to move to 10,000-year-old sacred indigenous territory with numerous tribes: “Blackfeet, Chippewa-Cree, Crow, Flathead, Gros Ventres, Kalispel, Kootenai, Little Shell Band of Chippewa, Northern Cheyenne, Piegan, Salish, Spokane, Bannock, Nez Percé, Palouse, and Northern Shoshoni tribes.”

According to Ripple Effects: How to Save Yellowstone and America’s Most Iconic Wildlife System, author and Bozeman, Montana resident Todd Wilkinson, argues one of Montana’s greatest ecological challenges is not grizzly bears per se but human population growth. Wilkinson explains that at current growth rates, Bozeman, Montana’s population will be “…equal to all the residents of the entire Greater Yellowstone today.” That’s 420,000 people – up from today’s cozier 50,000– by 2065. The silver lining on the grim population cloud is some residents are courageously facing this challenge. In fact, young residents just won the legal right to uphold the Montana Environmental Policy Act (MEPA) in a historic win producing its own ripple effects.

“The Last Best Chance for the Last Best Place” is what the Alliance calls the Northern Rockies Ecosystem Protection Act (NREPA). NREPA, first introduced in 1993, now has eleven Senate co-sponsors. Why hasn’t it passed? Because of its sweeping ecological implications. NREPA proposes to extend the highest protected land status to 23 million public acres; designate 1, 800 miles as Wild and Scenic Rivers; restore one million wilderness acres by “removing 6, 300 miles of old logging roads”; and replenish damaged fish and wildlife migratory routes.

Mike Garrity, who lives in Helena, Montana, is a CounterPunch author and Executive Director of the Alliance for the Wild Rockies. Founded in Missoula, the organization serves the entirety of North America’s longest (3,000-mile) mountain system.

I interviewed Garrity by email the week of November 6, 2023.

Q. Your organization is an alliance representing the Wild Rockies bioregion. Do people understand bioregionalism? Do you find bioregionalism is a good organizing strategy to mitigate fragmentation and myopia?

A. A bioregion is a region defined by characteristics of the natural environment rather than by human-made divisions. We are working to educate people that wildlife and fish don’t recognize political boundaries, They instead recognize ecological or bioregional boundaries. The best way to help native species is to talk in scientific rather than political terms.

Q. How is grassroots support for NREPA? How are people organizing to support it? How are the Southern Rockies organized? Will there be a SREPA?

A. The grassroots support for NREPA is growing every year. People and environmental groups are supporting NREPA by asking their members of Congress to cosponsor it. Right now there is not a SREPA but we hope that someone will follow our lead and write a Southern Rockies Ecosystem Protection Act.

Q. The scientific reality of animal/ biological connection corridors is bringing recalcitrant parties to the table. How have relations among environmentalists, ranchers, property owners and businesses changed in the Rockies? Any hope here?

A. No, not much. More and more ranches in the Northern Rockies are being bought by corporations or billionaires. We need to move away from the idea that land should be managed based on the profit motive rather than an ecological motive.

Q. Let’s review specific threats to each of the five ecosystems NREPA represents and see what specific actions the Alliance is taking this year.

A. Greater Yellowstone – Grazing, clearcutting, intentional burning, and logging is the main threat and the Alliance has filed lawsuits to stop all three where they threaten recovery of native species like grizzly bears, sage grouse, northern goshawks, pinyon jays and lynx.

Hells-Canyon-Wallowa’s biggest threat is logging of native forest which the Alliance is actively fighting to protect.

Salmon-Selway – The biggest threat was from the federal government who refused to acknowledge that grizzly bears have returned on their own to the Salem-Selway ecosystem but thanks to the Alliance’s victory in federal district court, the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service is under court order to come up with a draft management plan to protect grizzly habitat in the Salmon Selway ecosystem which is the key linkage zone to ensure recovery of all grizzly habitat in the Northern Rockies.

Greater Northern Continental Divide has multiple threats, from industry and mining to clearcutting and bulldozing of more logging roads, all of which threaten native species and their habitat. The Alliance is actively fighting to protect habitat from exploitation throughout this ecosystem which is often called the American Serengeti.

Cabinet-Yaak-Selkirk – Clercutting and bulldozing logging roads are the biggest threats. Because of lawsuits won by the Alliance, logging in the Kootenai National Forest is down to 5 million board feet a year from their annual target of 70 million board feet a year.

Q. What is the Alliance’s response to development projects like Bozeman’s new photonics tech corridor requiring rare earth minerals? How does this job development approach threaten the Alliance’s own job development vision?

A. There are several different proposals to mine for rare earth minerals in ecologically sensitive areas that are currently protected by the Clinton roadless rule in the Northern Rockies. We of course are opposed to this and are concerned that these proposals are more of an attempt to mine investors but we are also concerned about the ecological damage that would occur if these mines are developed.

Q. What do you anticipate with excitement and what do you dread in the next year?

A. We just won a big case stopping a Forest Service project to clearcut an old-growth forest in an imperiled grizzly habitat in northwest Montana. Besides the threat to the Cabinet-Yaak grizzly population, the judge found that the Forest Service did not examine how clear-cutting old-growth forests would worsen global warming. Forests, especially old-growth forests, are carbon sinks. We not only need to reduce the amount of carbon we release into the atmosphere every year– but we also need to protect forests which absorb up to 14% of the carbon that America emits every year.

Q. As a concerned Northern Rockies bioregion resident, I encourage donations to your organization. What are your main funding sources? What’s on the Alliance’s wishlist this year?

A. Our main funding sources are individuals who make small donations. We don’t get a lot of grants from foundations because we are not afraid to oppose powerful politicians. Robert A. Goldberg, author of Grassroots Resistance: Social Movements in Twentieth-Century America, argues as social movements get bigger, they become more dependent on big foundations controlled by the wealthy. Unlike many environmental groups, the Alliance keeps to its mission to protect habitat for native species rather than grow the organization.

You can find how to donate to the Alliance and take action on issues here: Take Action – Alliance For The Wild Rockies.

Michelle Renee Matisons, Ph.D. can be reached at michrenee@gmail.com.